Carlos

Calvimontes Rojas*

|

|

No hay estudio del hombre que merezca

llamarse ciencia si no se basa en la demostración y argumentación

matemática.

Que nadie se atreva a adentrarse en los

fundamentos de mi obra si no es matemático.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

|

|

There

is no study of the man that deserves to be called science when it is not

based on the mathematical demonstration and argumentation.

That

nobody dares to study in dept the basic principles of my work if he is

not a mathematician.

Leonardo

da Vinci (1452 – 1519) |

|

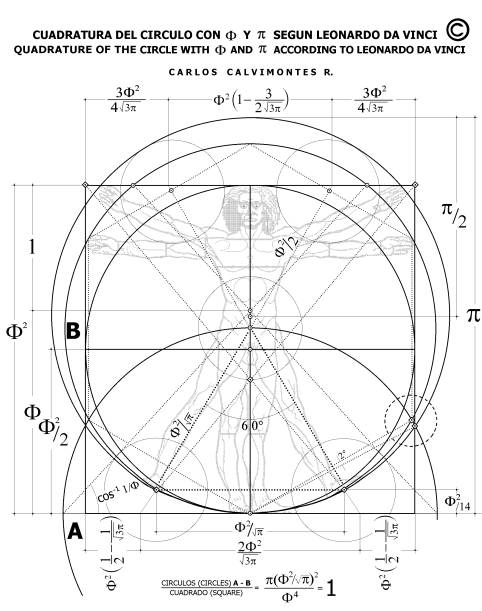

LEONARDO DA VINCI SE INSPIRO EN LA OBRA DE

VITRUVIO PARA SEÑALAR LAS PROPORCIONES HUMANAS; PERO ADEMAS

OCULTO EN ESA GEOMETRIA OTRA QUE, AL SER DECODIFICADA, DEMUESTRA

LA CONSTRUCCION DE UN CIRCULO DE IGUAL AREA QUE EL CUADRADO

DIBUJADO. CON ESA BASE SE RESOLVIO EL ANTIGUO PROBLEMA DE LA

‘CUADRATURA DEL CIRCULO’, SEGUN SU POSTULADO ORIGINAL: ‘A

PARTIR DE UN CIRCULO CONSTRUIR UN CUADRADO QUE TENGA LA MISMA

SUPERFICIE, SOLO CON EL EMPLEO DE UN COMPAS Y UNA REGLA SIN

GRADUAR'. |

|

LEONARDO

DA VINCI INSPIRED HIMSELF IN THE WORK OF VITRUVIO FOR INDICATING THE

HUMAN PROPORTIONS; BUT MOREOVER HIDDEN IN THAT GEOMETRY ANOTHER ONE THAT,

WHEN BEING DECODED, SHOWS THE CONSTRUCTION OF A CIRCLE OF EQUAL AREA

THAN THE SQUARE DRAWN. WITH THAT BASIS THE ANCIENT PROBLEM OF THE 'QUADRATURE

OF THE CIRCLE', ACCORDING TO ORIGINAL POSTULATE: 'ON BASIS OF A CIRCLE CONSTRUCT A SQUARE THAT HAS THE SAME

AREA, ONLY WITH THE USE OF A COMPASS AND A RULER WITHOUT GRADUATION' WAS

RESOLVED. |

|

*Con la colaboración de María

José Calvimontes C. y de Alfredo Calvimontes C.

*With

the cooperation of Maria José Calvimontes C. and of Alfredo Calvimontes

C. |

LEONARDO

Y VITRUVIO

El conocido esquema de Leonardo que muestra las

proporciones humanas se relaciona con el postulado que, quince siglos

antes, hizo sobre esa materia el arquitecto romano Marcus Vitruvius

Pollio en su obra De architectura. Leonardo mostró el

vínculo bajo el número 340 de su libro Tratado de Pintura [1] que,

poniendo entre paréntesis los criterios que no se encuentran en la obra

precedente, en forma escueta dice en la parte que interesa:

Según Vitruvio....... Si abres tanto las piernas

(que tu altura mengüe en 1/14,) y tanto extiendes y alzas los brazos

que con los dedos medios alcances la línea que delimita el extremo

superior de la cabeza, has de saber que el centro de los miembros

extendidos será el ombligo (y que el espacio que comprenden las piernas

será un triángulo equilátero). La longitud de los brazos extendidos

de un hombre es igual a su altura.

|

|

LEONARDO

AND VITRUVIO

The known scheme of Leonardo that

shows the human proportions relates with the postulate that, fifteen

centuries before, the Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio made on

this matter in his work De architectura. Leonardo has shown the link

under the number 340 in his book Treaty of Painting [1] that, putting

into parenthesis the criteria that are not found on the preceding work,

in concise form says in the part that is of interest:

According to Vitruvio..... When you open so much the

legs (so that your height decreases by 1/14), and extend and raise the

arms so that with the middle fingers you reach the line that limits the

upper end of the head, you have to know that the center of the extended

members will be the navel (and that the space that comprise the legs

will be an equilateral triangle). The length of the extended arms of a

man is equal to his height.

|

|

Vitruvio, según la traducción al castellano de

Angeles Cardona [3] -que

en esencia no difiere de otras-,

en forma extensa expuso:

El ombligo es el punto

central natural del cuerpo humano. En efecto, si se coloca un

hombre boca arriba, con sus manos y sus pies estirados, situando

el centro del compás en el ombligo y trazando una circunferencia,

ésta tocaría la punta de ambas manos y los dedos de los pies. La

figura circular trazada sobre el cuerpo humano nos posibilita el

lograr también un cuadrado; si se mide desde la planta de los

pies hasta la coronilla, la medida resultante será la misma que

la que se da entre las puntas de los dedos con los brazos

extendidos; exactamente

su anchura mide lo mismo que su altura, como los cuadrados que

trazamos con la escuadra.

|

|

Vituvio, according to the

translation into Spanish by Angeles Cardona [3] -that essentially does

not differ from others-, in an extended fashion explained:

The navel is the central point of

the human body. In fact, if a man is placed face up, with his hands and

feet stretched, placing the center of the compass at the navel and

drawing a circumference, this will touch the tip of both hands and the

fingers of the feet. The circular figure drawn on the human body enables

us to also achieve a square: if we measure from the sole of the feet up

to the crown of the head, the resulting measure will be the same than

the one between the tips of the finger with the extended arms; its width

measures exactly the same as its height, such as the squares we draw

with the set square. |

ANTECEDENTES

Y ENTORNO

A partir del descubrimiento en 1414 (sin sus

ilustraciones por habérselas perdido) de una copia manuscrita del libro

de Vitruvio, con los principios de la arquitectura clásica el interés

por el pasado, de artistas, arquitectos y mecenas, motivó que la labor

de hacer inteligible a esa obra recayera primeramente en eruditos

humanistas, arqueólogos, anticuarios, filólogos y gramáticos, dando

origen a una variedad de tratados [5], desde la obra de Alberti que

recuerda a Vitruvio, y a numerosas ediciones del libro de éste, una en

el siglo XV y por lo menos once en el XVI.

Asumiendo que Leonardo realizó

su dibujo entre 1485 y 1490, aparte de haber podido conocer manuscritos

de la obra de Vitrubio, la única edición de ella en su época que pudo

haber tomado en cuenta sería la que se supone se imprimió en Roma

entre 1486 y 1492, que empieza con una nota del editor, Iohannes

Sulpitius di Veroli, y se considera la edición príncipe de la obra.

Sulpitius usó los manuscritos más conocidos, pero dejó espacios en

blanco para los términos griegos, los epigramas y las ilustraciones; de

éstas sólo intentó una, un círculo.

También Leonardo pudo considerar la obra de Alberti

De re aedificatoria impresa en 1485; pero es posible que anteriormente

la haya tenido a su alcance, porque habían pasado más de treinta años

desde su presentación. Por otra parte, es evidente que leyó los

tratados que Francesco di Giorgio Martini hizo sobre la base de la obra

de Vitruvio. Con lo cual Leonardo habría tenido, aparte del

conocimiento de manuscritos de ésta, por lo menos tres referencias

sobre la misma y, sabiendo tanto de anatomía humana, pudo interpretar hábilmente

el criterio del arquitecto clásico.

Aunque la edición de Fra Giovanni Giocondo, impresa

en Venecia en 1511, fue realizada cuando aún vivía Leonardo y éste

pudo haberla conocido, ya no habría influido en su dibujo de las

proporciones de la figura humana. Fra Giocondo fue el primero en hacer

una edición crítica de la obra de Vitruvio, empleó material de

diferente procedencia, no dejó lagunas, reconstruyó las partes

griegas, produjo más de 136 ilustraciones, elaboró un glosario y una

tabla matemática para comprender el texto. El éxito de esa edición

determinó su reimpresión en 1513, 1522 y 1523.

El texto y las ilustraciones de

Fra Giocondo influyeron en las ediciones de De Architectura en el siglo

XVI. Sin embargo, pese a que el dibujo de Leonardo fue conocido y

utilizado por artistas y estudiosos desde esa época, hasta donde se

conoce no fue tomado en cuenta en ediciones posteriores ilustradas, que

no tienen la correcta interpretación que él hizo del postulado de

Vitruvio sobre las proporciones humanas. Actualmente, las más antiguas

y conocidas de esas ilustraciones son las de Francesco di Giorgio

Martini y Cesare di Lorenzo Cesariano.

Se puede entender que, en los

siglos en los que hubo mayor interés práctico por la obra de Vitruvio,

los editores hubiesen pretendido unidad y originalidad en la recreación

de las ilustraciones que se habían perdido; pero no se utilizó el

dibujo de Leonardo en ediciones tan tardías como la de Perrault que,

casi dos siglos después, ensayó una solución insatisfactoria de lo

que ya estaba resuelto, al mantener la misma distancia entre las líneas

horizontales que corresponden a la coronilla y a los pies, sin tomar en

cuenta que la estatura disminuye si se abre las piernas. |

|

BACKGROUND

AND SURROUNDINGS

From the discovery in 1414 on (without its

illustrations due to having lost them) of a handwritten copy of the book

of Vituvio, with the principles of the classic architecture the interest

for the past, of artists, architects and maecenas, motivated that the

task of making intelligible that work firstly fall on scholars,

humanists, archaeologists, antiquarians, philologists and grammarians,

giving origin to a variety of treaties [5], from the work of Alberti

that remembers Vituvio, and to numerous editions of the book of the

latter, one on the XV century and at least eleven on the XVI century.

Assuming that Leonardo made his drawing between 1485

and 1490, besides of having been able to know manuscripts of the work of

Vitruvio, the only edition of which in its time that could have been

taken into account would be the one that is supposed to be printed in

Rome between 1486 and 1492, that begins with a note of the editor,

Iohannes Sulpitus di Veroli and is considered the first edition of the

work, Sulpitus used the most known manuscripts, but left blank spaces

for the Greek terms, the epigrams and the illustrations; of these he

only tried one, a circle.

Also Leonardo could consider the work of Alberti De re

aedificatoria printed on 1485; but it is possible that he previously had

it available, because more than thirty years elapsed since its

presentation. On the other hand, it is evident that he read the treatise

Francisco di Giorgio Martini made on basis of the work of Vitruvio. With

which Leonardo has had, besides the knowledge of manuscripts, at least

three references about it and, knowing so much of human anatomy, could

skillfully interpret the criterion of the classic architect.

Although the edition of Fra Giovanni Giocondo, printed

in Venice on 1511, was done when Leonardo still lived and could have

known it, he no longer could have influenced on the drawing of the

proportions of the human figure. Fra Giocondo was the first in doing a

critical edition of Vitruvio's work, he employed material of different

origin, did not leave gaps, reconstructed the Greek parts, produced more

than 136 illustrations, prepared a glossary and a mathematical table for

understanding the text. The success of this edition determined its

reprint on 1513, 1522 and 1523.

The text and illustrations of Fra Giocondo influenced on

the editions of De Architectura on the XVI century. However, though the

drawing of Leonardo was known and used by artists and scholars since

that time, as far as it is known has not been taken into account in

subsequent illustrated editions, that lack the correct interpretation he

made of the postulate of Vitruvio about the human proportions. At

present, the oldest and most known of these illustrations are those of

Francesco di Giorgio and Cesare di Lorenzo Cesariano.

It can be understood that, on

the centuries where higher practical interest existed for the work of

Vitruvio, the editors had pretended unity and originality in the re-creation

of the illustrations that had been lost; but the drawing of Leonardo was

not used in editions so late as the Perrault's that, almost after two

centuries, tried an unsatisfactory solution of what had already been

solved, keeping the same distance between the horizontal lines that

correspond to the crown of he head and the legs, without considering

that the height decreases if the legs are opened. |

GEOMETRIA

MANIFIESTA Y OCULTA

Hasta la actualidad se

ilustra ediciones de De architectura con antiguos dibujos pero no

con el de Leonardo, que interpretó a Vitruvio, aunque con la

incorporación del valor de p

como diámetro del círculo y los

definidos por la Sección Aurea localizada en el ombligo; separación

entre el valor del Numero de Oro, F, y el de 1 en la estatura de

la figura humana. Estas modificaciones, señaladas claramente en

el esquema de Leonardo, determinan la diferencia entre el valor de

F y el de

p/2, (0,04723....), que equivale a un 1,8 % de la

estatura del hombre representado.

De lo que

no escribió Vitruvio: la disminución en 1/14 de la estatura de

la figura es una innovación de Leonardo. Aunque siempre se ha

pensado que tomando como centro el ombligo se forma un triángulo

isósceles en vez de uno equilátero, sin éste no se lograría la

fracción establecida por él. Se dice que Vitruvio no escribió

algo relativo a que ‘con los dedos de las manos se alcanza la

línea que delimita el extremo superior de la cabeza’; pero, al

referirse al cuadrado implicaría que los brazos extendidos, tanto

hacia arriba como lateralmente, alcanzan a los lados del cuadrado.

Leonardo dejó

deliberadamente, en su dibujo y escritos, cinco claves que se tomó

en cuenta en la decodificación de su esquema: la ubicación del

punto que define la Sección Aurea en el ombligo, la diferente

localización del centro del círculo y el diámetro de éste

igual a p,

el valor de 1/14 en la disminución de la estatura y el

planteamiento de la formación de un triángulo equilátero. Con

esos datos, se pudo hallar la solución gráfica de la ‘cuadratura

del círculo’; con valores matemáticos concluyentes, para un

problema cuya solución se consideró imposible de lograr, durante

milenios, pero que Leonardo conoció y ocultó en forma críptica.

|

|

REVEALED

AND HIDDEN GEOMETRY

Up to now illustrations of De

archithecture with old drawings but not with the one of Leonardo, that

interpreted Vitruvio though with the incorporation of the value of p as

diameter of the circle and those defined by the Golden Section located

at the navel, separation between the value of the Golden Number, F, and

the value of 1 in the height of the human figure. These modifications,

clearly indicated in the scheme of Leonardo, determine the difference

between the value of F and of

p/2, (0.04723....), that is equivalent to

an 1.8 % of the height of the represented man.

From what Vitruvio did not write,

the decrease of 1/14 in the height of the figure is an innovation of

Leonardo. Although it has always been thought that taking the navel as

center of the figure an isosceles triangle is formed instead of an

equilateral one, without this one the established fraction would not be

achieved. It is said that Vitruvio did not write something related to

that 'with the fingers of the hand the line that limits the upper end of

the head is obtained'; but, when referring to the square this would

imply that the arms extended, both upside and laterally, reach the sides

of the square.

Leonardo deliberately had left,

in his drawing and writings, five codes that were taken into account in

the decoding of his scheme: the location of the point that defines the

Golden Section in the navel, the different location of the center of the

circle and its diameter equal to p, the value of 1/14 in the decrease of

the height and the exposition of the formation of an equilateral

triangle. With this data, the graphic solution of the 'quadrature of the

circle' could be found, with conclusive mathematical values, for a

problem whose solution was considered as impossible to be achieved

during millenniums, but that Leonardo knew and hid in cryptic form. |

DEL

CUADRADO AL CIRCULO

Con centro en el punto medio

del lado inferior del cuadrado y como radio la distancia hasta el

extremo inferior de una de las cuerdas laterales del círculo con diámetro

p, se traza una circunferencia para conseguir el círculo A, con

área igual a la del cuadrado dado. Esa misma circunferencia, en su

intersección con el eje vertical del cuadrado, señala el centro del círculo

B que, tangente al lado inferior del cuadrado, obviamente tiene

igual superficie que éste. Con el centro del círculo como vértice

de un ángulo de 60°, que tiene por bisectriz al eje vertical, se forma

un triángulo equilátero que tiene de base la cuerda con flecha igual a

F2/14.

Con el procedimiento indicado se logra un círculo de igual área que la

de un cuadrado dado, con la intervención de F

y de p,

cumpliéndose además lo establecido por Leonardo.

Además, en el dibujo de

Leonardo, se observa que las líneas que unen los vértices inferiores

del triángulo equilátero con el punto localizado en el eje vertical, a

una distancia del centro del círculo dado igual a la cuarta parte de un

lado del exágono, en su proyección alcanzan los vértices superiores y

opuestos del cuadrado; y que la alineación de la recta que une la

intersección de la prolongación del lado inferior del cuadrado con la

circunferencia del círculo A, forma un ángulo igual a cos-1

de 1/F,

pasa por la Sección Aurea y confirma la ubicación de la intersección

de la circunferencia del círculo B con un lado del cuadrado.

Se debe tomar en cuenta que las

alineaciones, circunferencias, ángulos y tangencias, que se encontró

en el diseño de Leonardo, y se utilizó en la construcción para

encontrar puntos significativos de su decodificación, determinan la

coherencia geométrica de todo el conjunto y, además, tienen

correspondencia con partes definidas de la figura humana.

La solución específica que se

decodificó, para que a partir de un cuadrado con lado F2,

con la participación de un círculo con diámetro p,

se logre otro círculo con igual área que la de ese cuadrado, tiene

como clave que el radio que genera el círculo A, al rotar 2°

sobre el mismo centro, determina el radio del círculo B y un

lado del exágono regular inscrito en éste. La traslación del sistema

del círculo con diámetro p

y el cuadrado de lado F2,

a otro donde el cuadrado dado y el círculo oculto tienen áreas

iguales, constituye el artificio para esa solución. |

|

FROM

THE SQUARE TO THE CIRCLE

With center in the middle point

of the lower side of the square and as radius the distance to the lower

end of one of the lateral chords of the circle with diameter p, a

circumference is drawn for obtaining the circle A, with area

equal to that of the given square. That same circumference, in its

intersection with the vertical axis of the square, indicates the center

of the circle B that, tangent to the lower side of the square,

obviously has an area equal to such square. With the center of the

circle as vertex of an angle of 60°, that has as bisector to the

vertical axis, an equilateral triangle is formed having as basis the

chord with sagitta equal to F2/14.

With the indicated procedure a circle is achiever with area equal to the

given square, with the intervention of F

and of p,

complying further what was established by Leonardo.

Moreover, on the drawing of

Leonardo, it is noticed that the lines that put together the lower

vertexes of the equilateral triangle with the point located in the

vertical axis, at a distance from the center of the given circle equal

to the fourth part of one side of the hexagon, in their projection reach

the upper and opposed vertexes of the square, and that the alignment of

straight line that puts together the intersection of the prolongations

of the bottom side of the square with the circumference of the circle A,

forms an angle equal to cos-1 of 1/F,

passes by the Golden Section and confirms the location of the

intersection of the circumference of the circle B with one side

of the square.

It must be taken into account

that the alignments, circumferences, angles and tangencies found in the

drawing of Leonardo and used in the construction for finding significant

points of its decodification, determines the geometric coherence of all

the assembly and, moreover, has correspondence with defined parts of the

human figure.

The specific solution that has

been decoded, so that on basis of a square with side F2,

with the participation of a circle of diameter p,

other circle be obtained with equal area than that of that square, has

as key that the radius that generates the circle A, when rotates

2° on the same center, determines the radius of the circle B and

one side of the regular hexagon inscribed in it. The translation of the

system of the circle with diameter p

and the square of side F2,

to another one where the given square and the hidden circle have equal

areas, constituting the trick for this solution. |

|

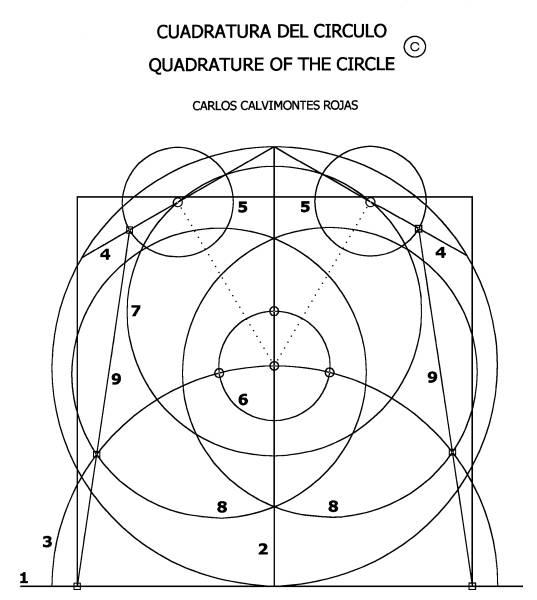

DEL

CIRCULO AL CUADRADO

Para atender al postulado

original del problema, que dice que partiendo de un círculo dado sólo

‘con compás y regla sin graduar’ se obtenga un cuadrado que tenga

la misma superficie, se hizo abstracción del círculo y del cuadrado

dibujados por Leonardo y se partió del círculo que él ocultó, con la

incorporación de: una línea tangente a ese círculo, una perpendicular

levantada en el punto de tangencia, dos lados del exágono inscrito

y de un arco circular con igual

radio que el del círculo dado con

centro en el mismo punto de tangencia.

Con un radio igual a la cuarta

parte de un lado del exágono se dibujó tres círculos auxiliares

iguales; dos de ellos con sus centros en la mitad de los lados dibujados

del exágono, en la parte opuesta a la tangente; y, con el mismo centro

del círculo dado, el tercero. Con centro en la intersección de éste

con la perpendicular, tomando como radio la distancia hasta la mitad de

las cuerdas, se hizo otro círculo. Con el radio anterior, con centros

en las intersecciones del arco circular con el mismo tercer círculo

auxiliar, se trazó otros dos círculos. Las intersecciones de éstos

con el arco circular señalan los puntos clave para definir la

‘cuadratura del círculo’.

En efecto, la línea que une

cada uno de dichos puntos con las intersecciones de los círculos

trazados sobre las cuerdas con éstas (en su parte más alejada de la

perpendicular), en su prolongación hasta la línea tangente definen

sobre ésta la longitud del lado del cuadrado de igual área que la del

círculo dado. |

|

FROM

THE CIRCLE TO THE SQUARE

For taking care of the original

postulate of the problem that states that starting from a given circle

only 'with compass and ruler without graduation' a square be obtained

having the same area, abstraction has been made from the circle and the

square drawn by Leonardo and it has been started from the circle

he did hide, with the incorporation of a line tangent to that

circle and a perpendicular lifted at the point of tangency, two sides of

the inscribed hexagon and a circular arch of same radius than the given

circle with center in the same point of tangency.

With a radious equal to the

fourth part of one side of the hexagon three auxiliary equal circles

were drawn; two of them with its centers at the middle of the drawn

sides of the hexagon, in the part opossed to the tangent; and, with the

same center of the given circle, the third one. With center in the

intersection of this with the perpendicular, taking as radious the

distance to the middle of the chords. another circle was made. With the

former radious, with center in the intersections of the circular arch

with the same third auxiliary circle, another two circles were made. The

intersections of these with the circular arch indicate the key points

for defining the ‘quadrature of the circle’.

Indeed, the line that joins each

one of such points with the intersection of the circles drawn on with

these (on its part that are more away from the perpendicular), in its

prolongation up to the tangent line defines about this the length the

side of the square of the same area than that of the given circle. |

|

|

BIBLIOGRAFIA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1.

DA VINCI, LEONARDO. Tratado de la

Pintura. Edición preparada por Angel González García. Editorial

Nacional. Madrid, 1980.

2.

DA VINCI, LEONARDO. Tratado de la

Pintura. Traducción al castellano sobre el original francés de André

Keller por Angeles Cardona. Reimpresión íntegra de la edición

italiana de Bolonia (1786), publicada en París por Rafael Trichet de

Fresne. Editora de los Amigos del Círculo del Bibliófilo. Barcelona,

1979.

3.

VITRUVIO POLLIO, MARCO. Los Diez

Libros de Arquitectura. Traducción al castellano por José Oliver

Domingo. Introducción de Delfín Rodríguez Ruiz, Alianza Editorial.

Madrid, 1995.

4.

VITRUVIO POLLIO, MARCO. Los Diez

Libros de Arquitectura. Traducción directa del latín al castellano, prólogo

y notas de Agustín Blánquez. Editorial Iberia S. A., Barcelona, 1991

5.

WIEBENSON, DORA. Los Tratados de

Arquitectura. Editorial Hermann Blume, Madrid, 1988. |

|

|

|

|

|

IR AL

ÍNDICE

http://urbtecto.es.tl

urbtecto@gmail.com |